Cox’s, coming down

A landmark department store tumbles

[Robert] Cox believes that the only way a business can continue to flourish and meet the challenge of competing firms is by more showmanship in retailing.

“Showmanship carelessly handled can be as dangerous as a dynamite cap and a hammer in the hands of a child,” he said. “Showmanship is needed in retailing because of today's tremendous competition not so much to gain the customer's money as for her minutes.”

—“McKeesport: A City of Flourishing Businesses,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, April 17, 1960

|

|

|

Cox’s clock, at the corner of Fifth and Walnut streets, was a landmark in Downtown McKeesport akin to Kaufmann’s clock in Pittsburgh. At last report, the clock was owned by McKeesport businessman Eldo Bisada. More Cox’s photos, including seldom-seen interiors, are also available. (Jason Togyer photo.) |

|

By Jason Togyer

It's 10:30 pm on a Sunday night in July 1994, and I am standing at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Walnut Street in downtown McKeesport, watching the show.

The "show" is the demolition of the Walnut Street facade of Cox's department store by D.J. Betters Wrecking, and the audience includes about two dozen spectators. I was on my way home from work at Kennywood when I saw the lights and the gawkers and drove around the block to investigate. Now I'm in the crowd, which includes people of all shapes, sizes, and ages, and not a few kids in pajamas.

A crane, wrecking ball attached, sits in front of the Golden Rule store on Walnut, which is strewn with blue ceramic tiles from the front of the building and chunks of concrete. Only a few beams on the Walnut Street side remain, along with the awning over the sidewalk and the street-level display windows.

The crews have been tearing down Cox's for several weeks, after a last-minute effort by a local businessman to save the building failed. When I left for work this morning, only the front two walls were standing.

I join the group of people standing in front of the Integra Bank across the street and get the scoop. According to one man, a beat cop walking past Cox's the previous night had heard ominous noises coming from the walls and called the fire chief.

He called the building inspector, who called the contractor and told them to "get this building down," the man says, "before it falls down." His friend confirms the story, saying he "heard it on my scanner."

Two other guys, one black, one white, are handicapping the crew's progress and the Cox's building in general. "They're between a shit and a sweat now," says the white guy, pointing at the crew, which is standing in semi-darkness, looking solemnly at the pile of debris.

The wrecking ball is raised and begins to knock the awning to the ground. At first, the ball succeeds mostly at puncturing holes in the awning, but finally it gives way and falls to the sidewalk. The crane operator seems to be stalling for time, pondering his next move.

"See?" says the white guy. "They have no idea what to do next."

"One false move and that whole front wall is going to come down," says the black guy, nodding. As if to confirm his suspicion, a member of the wrecking crew runs out to Fifth Avenue and moves the company's trucks away from the building.

: : : : : :

It's an ignominious end for a structure whose merchandise once symbolized the height of elegance for McKeesporters. In 1872, Mary Ann Cox, a seamstress, began selling clothing and millinery from her house on Market Street.

By 1884, she had become the town's leading seamstress and opened a little shop on Fifth Avenue. Little did she know that her sons and grandsons would turn that store into a retail empire, but soon the Cox family owned three upscale clothing stores on Fifth Avenue - one each for men, women, and children - that employed 400 people.

: : : : : :

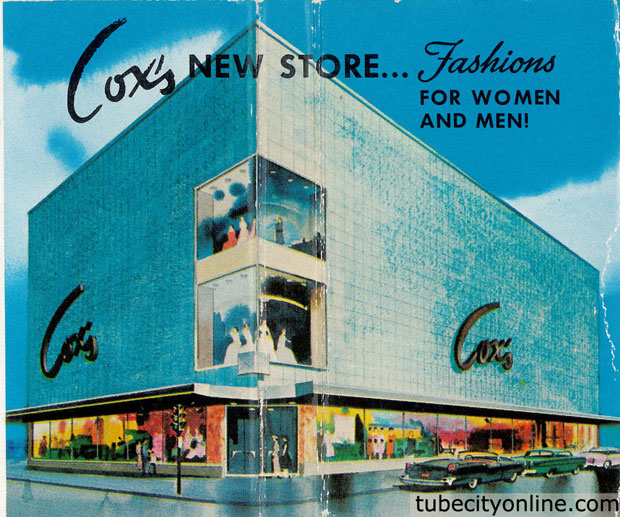

With National Tube running flat-out during the postwar boom period, Robert Cox decided it was time to consolidate the stores' operations, and in the early `50s he bought White's Opera House at the corner of Fifth and Walnut, demolishing it to build his flagship store. The modern four-story department store, built in the International Style, opened in 1955.

"It's here! It's here! The big day!" trumpeted an ad in The Daily News, and it was quite an event for the city.

From its chrome trimmed, blue-tiled front to its marble and terrazzo floors, Cox's was a class-act all the way. The street was closed periodically for fashion shows, with the models using the awnings outside as runways. At night, indirect lighting illuminated the front of the building, including the giant stylized "Cox's" scripts.

Inside, besides the latest fashions, the architects had included an elevator and - fantastically - an escalator! In a city full of wooden-framed five-and-tens, anchored at one end by a Sears and at the other by Monkey Wards, it must have seemed like Macy's on the Mon.

The futuristic Cox's building inspired other business owners to modernize their stores. Soon, the filigree had come off of the First National Bank of McKeesport, on the opposite corner of Fifth and Walnut, replaced by sharp angular concrete.

The Famous, a discount store at Fifth and Market, was covered with blue tiles in imitation of its hoity-toity competitor. Another Fifth Avenue department store, the Braddock-based Jaison's, also covered its entrance with tile, but used different colors -- yellow and white -- though its script logo looked similar.

By 1972, Bob Cox was riding high. He had opened six branches in suburban malls, and was expanding the McKeesport store to cover most of the block. Cox's had retained graphic artist Arnold Varga to update its image and it was emerging as a challenger to Horne's and Kaufmann's, Pittsburgh's biggest department stores.

: : : : : :

But there were problems. Cox's couldn't compete with giant chains like J.C. Penney's, which was by then carrying a better line of merchandise. And even established companies like Gimbel's were collapsing in the face of stiff competition from discounters. In 1983, only the original Cox's store was left, and then it, too, was gone.

Bob Cox lived for many years in the fancy penthouse apartment above his closed headquarters. Often, he could be seen walking around downtown, early in the morning. Sometimes he was walking his dog; other times, he was spotted shadow-boxing in the alley or sitting on a park bench on Walnut Street.

An attempt to auction the building and its fixtures failed when no one bid.

: : : : : :

I start to wonder whatever happened to Mr. Cox when the white guy, whose name is Jimmy (I never heard his last name) says that he was the building manager at the downtown store from the late `60s until its final weeks.

"That building was not solid," he says. "The old part was okay, but that new part was garbage. You could have kicked your way out. The walls were just plasterboard and aluminum. I remember one time, a truck sideswiped the back of the building, tore off a bunch of the [outside] panels, and ended up halfway into the store.

"It was fun to walk up on the roof at night, and hear that building creak and groan. You could stand up there and look down at the sidewalk and see who was downtown that night. Hell, I'm going back 20 years now. There were all kinds of people out here at night then."

"Yeah," says someone else, "this is probably the biggest crowd downtown at night in years." The crowd laughs.

The crew has stopped banging on the awning, and has taken one of the old floodlights from the facade and hooked it up to a portable generator. A gangly kid in a hard-hat is balancing a trash-can on top of a card table, and the floodlight on top of the trash can. The contraption wobbles slightly in the breeze. "That's why they're in demolition, not construction," someone sneers.

: : : : : :

Jimmy starts to talk about his days at Cox's. I ask him about Bob Cox. "He always had dogs. He had this one, a damned Schaunzer, and he used to make me walk that thing up Tube Works Alley at night. Hell, I might as well have had a sign that said `easy mark' on my back. He fed that damn thing in the cafeteria, and then I'd have to clean up after it.

"Toward the end, he was getting clothes in, after hours, through the back door. They were coming in old television boxes. No shit. That's when I got the hell out."

A man with a torch is cutting rebar from the remaining steel beams. The gangly kid hoses down the wreckage with a fire hose. A squad car rolls to a stop, the cop greets some of the kids standing on the corner, and they run up to talk to him. "Jimmy" prepares to leave. I tell him that I had tried to get the clock on the corner of the building for the local historical society, only to be outbid.

"You didn't want it, anyway," he says. "That clock was a piece of shit. The mechanism was down in the basement, and it never worked right. In fact, I was probably the last person to go out on that awning before the store closed. I got bored one night and went out to fix the clock. I had to hunt all over for the key to the door."

He climbs into a Chevrolet Suburban and leaves. The wrecking crew has the headache ball at work again, banging the floor out of the corner display window.

By 1:00 am, progress is slow. The audience is drifting away. I get ready to leave, too, and ask the foreman if it was true that the building was ready to collapse.

"Nope," he says. "We've been planning this. We knew we'd have to close the road to finish this part. It's easier if we do it at night and on the weekends."